Article content

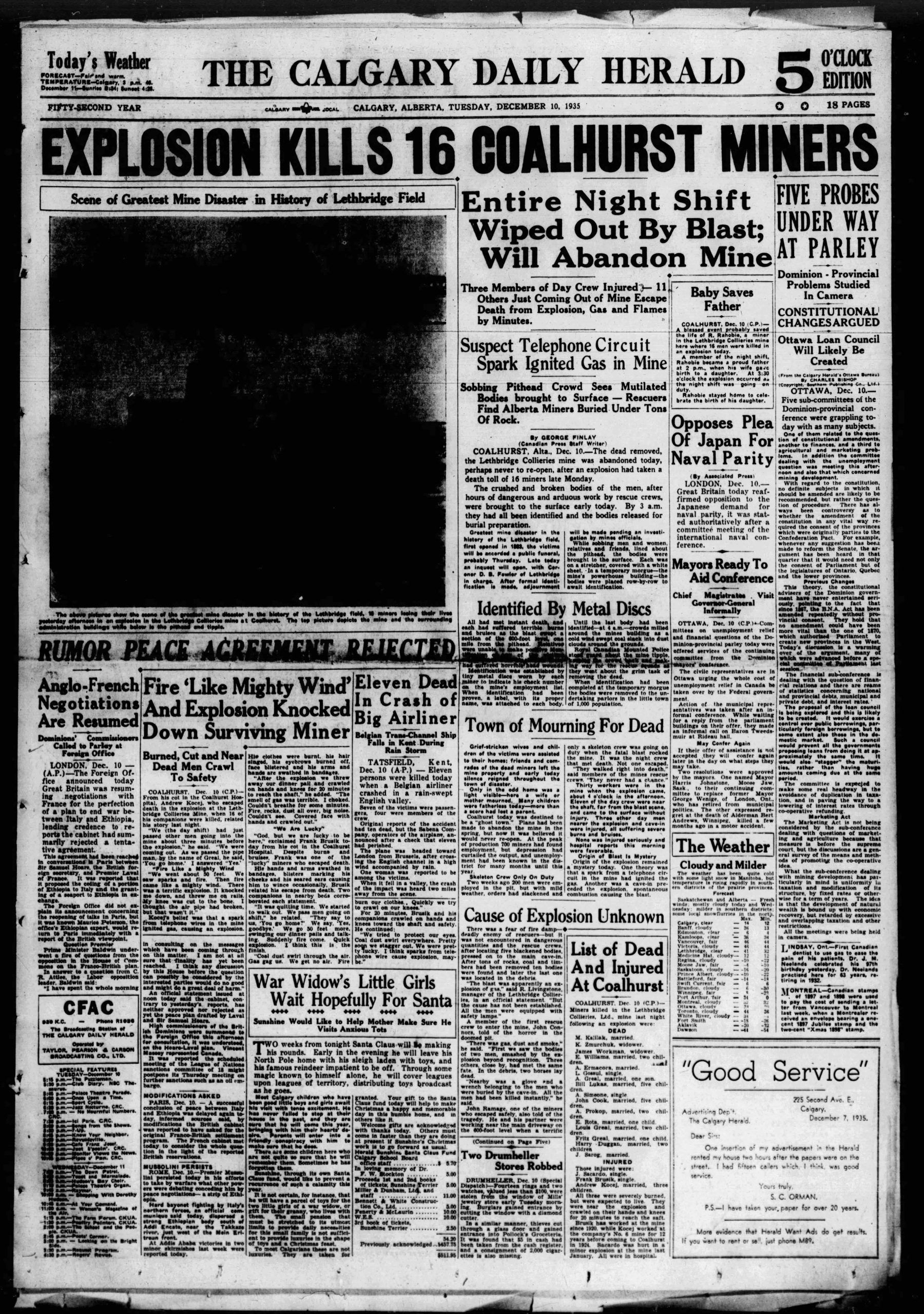

In December 1935, a mining accident in Coalhurst (about 15 kilometers north of Lethbridge) left 16 men dead. The accident touched the lives of nearly every one of the 1,200 residents in that town, including a young girl who reflected on the tragedy 70 years later for the following news report. She recalled that while life was difficult, the small kindnesses shown by others always stayed with her and contributed to her ability to remember what really mattered at Christmas. Author, photojournalist and former Calgary Herald journalist David Bly interviewed her for this story, originally published in 2005.

Advertisement 2

Article content

Small acts of kindness brightened difficult times

Article content

Calgary Herald

Sunday, December 4, 2005

Page: B4

By David Stay

It was December 9, 1935. Sixteen miners entering the Coalhurst colliery for the evening shift were murdered when an explosion tore through the shaft.

No family in the southern Alberta town a few kilometers west of Lethbridge was untouched by the disaster.

Even though she was not quite seven at the time, June Munroe (now June Clark of Calgary) remembers the chain of events clearly.

This is one of many memories she has of a hard life in a small coal mining town.

As Christmas approaches, some of the memories are painfulbut she says it was in Coalhurst that her faith was formed – even though her family moved to Calgary a few months after the explosion – and where she encountered unforgettable kindness in the midst of poverty and injustice.

Advertisement 3

Article content

Life was not easy for most of Coalhurst’s 1,000 residents in December 1935. Contributed to the misery of the Depression was the uncertain coal market, made worse by a steady chinook that brought mild weather and reduced demand for coal.

But for Jean Munroe and her four daughters, life was particularly difficult.

She married at 18 and was pregnant with her fourth child – June – when her marriage ended in a scandalous divorce.

“She was 26 when she was left alone with four children,” said June. “Back then was divorce shamefulsuch a shameand the woman was often blame.“

She said it was such an injustice, especially since her mother the innocent victim.

It might have been more bearable for the family in the anonymity of a city, June said, but in a small town everyone knew everything.

Advertisement 4

Article content

“It was a real stigma in a small town,” said June, “and the children will pick it up.

“We weren’t really considered a normal family. I sometimes thought I would like to say my father was death — that would have made it easier for me.“

But he was very much alive and still living in Coalhurst. His child support payments, which sometimes did not come, were Jean Munroe’s only source of income.

There was little joy in the Munroe household—Jean was almost a recluse, and most of her energy was spent trying to support a household on a shoestring budget.

Sometimes Junie went to the big slag heap, the place where the waste material from the coal mine was showeredlooking for lumps of coal to heat the house.

The same slag heap was also the source of endless black dust stirred up by the constant wind.

Advertisement 5

Article content

“We would close the windows, but the dust would come in anyway,” said June.

But life brightened up a bit when the family rented the mansion next to the Pentecostal church. It was vacant because the congregation could not afford its own pastor and relied on one from Lethbridge.

“When we moved into the mansion, it was wonderful when I heard the music coming from the windows,” said June. “There was joy – those people were happy. Those hymns are still in my heart.“

She was also driven by the faith of her grandmother, Jemima McInnis, who, although bedridden, was a source of spiritual strength for June, who often visited her grandmother humble company house.

“My dear grandmother was precious,” said June. “For the short time she was in my life, she had a great influence.

Advertisement 6

Article content

“She was a lovely Christian who told me the stories from the Bible. She told me Jesus loved i – we never heard it anywhere else.

“Some people don’t welcome we. I could see that look in people’s faces, and it hurt in so many ways. They don’t have to.“

But life was not all bleak. She remembers a beautiful summer day when the Pentecostal church organized a picnic.

“I knew we couldn’t go, but then this big wagon pulled up in front of our house,” she said. “A lady from the Pentecostal church put it in her mind that they should stop for the Munroe children.“

With sandwiches that her mother quickly made, June and one of her sisters got on the wagon and drove to the river for a picnic among the trees and fresh air. It’s a day that still stands out in June’s mind.

Advertisement 7

Article content

“That pretty lady,” she said. “I never forget her. I sent her a thank you note a few years ago, about a year before she died, telling her how much that act of kindness meant.“

On the day of the mine explosion, June was at school.

“I remember sitting in our classroom, feeling a bump, a vibration, a sudden shake. Then we heard the whistle at the mine and we knew immediately that something had happened.

“It was close to four o’clock, and when we got out, people were running towards the mine.

“I remember that night we all stood on top of the shaft. We should have been home in bed, but we waited until they were all raised.“

No family in the town was untouched by the disasterand Christmas that year was dark.

Before the explosion, plans were underway to close the mine in favor of the more productive no. 8 mine in Lethbridge.

Advertisement 8

Article content

“They climbed the mine and then they sealed it,” said June. “I remember the town literally die. You would get up in the morning and there would be another building gone, up in flames.

“When you are a child, you listen to things. You would hear that another little shop was fired last night, and it burned down, and that was for the insurance.“

Coalhurst has since recovered as a pleasant commuter community, and as the home of CPR’s large rail-laying yard, but in those post-explosion years it became almost a ghost town.

People left in droves, including the Munroes.

Jean Munroe cared for her invalid mother, but when Jemima McInnis died in the spring of 1936, the family moved to Calgary.

Money wasn’t much more, but life was better. The family was no longer stigmatized by the divorce scandal.

Advertisement 9

Article content

And the city held wonders that June had never dreamed of.

“My sister and I went downtown and watched a policeman in uniform directing traffic on 8th Avenue,” she said. “For us it was so wonderful.“

She looks back on her few years in Coalhurst with mixed feelings. It was a time of sadness, but also a time when many small acts of kindness shone like bright jewels.

“If there was a hardest time, I would say this was it Christmas,” she said.

“It wasn’t that other people had so much more, there was just more love. We didn’t feel precious, we didn’t feel we were very precious.

“I can’t help but think things would have been better if we only had a father.“

But her grandmother instilled in her a hope and a determination for a better life.

“She sowed the seed that one day bore fruit,” said June.

“I have a lot wonderful man. We have been married for over 56 years and we have two pretty children.“

June shook her head heart broken as she talks about the commercialism that has overtaken the holiday season.

“We celebrate a simple Christmas,” she said. “We remember what it’s really about.

“Today you see people who should be much happier than they are, but I think they don’t know what it is to go without.“